I was nine years old when my life changed forever.

I had a virus for a couple of weeks when I began drinking a lot of water, which was my body’s attempt to get excess sugar out of my bloodstream. I was drinking 10 to 12 litres a day so, logically, I would go to the bathroom every half an hour to flush it out.

My parents thought I was just hydrating, and that it was good for dealing with the virus. But my symptoms became worse. I was playing in a tournament one day in March 2009 and could not finish the match. When I got home that evening, I threw up in front of our front door. I went to bed and started breathing heavily, not sure what was going on. One week later, I woke up in the hospital.

Unknowingly, my body had been attacking my pancreas and killing cells. I would be awake and aware for 10 seconds and then fall back asleep for an hour. That happened all morning and I had no idea what was going on.

When I finally woke up, I came to a realisation: I was starving. I had never been so hungry in my life. Next to me was a newborn with its mother and entire family. They had the most amazing meal ever: Incredible sandwiches, jellies, breads and the best of what we have in Germany. I remember just asking the nurse, ‘Hey, could I have one?’ She was like, ‘Nope, your blood sugar is still high. You have to wait for another couple of days’.

That was the first time I heard the term blood sugar. Not long after that, I was told I had Type 1 diabetes. I would be in the hospital for about a month and have been on a journey to optimising life with the disease ever since.

# # #

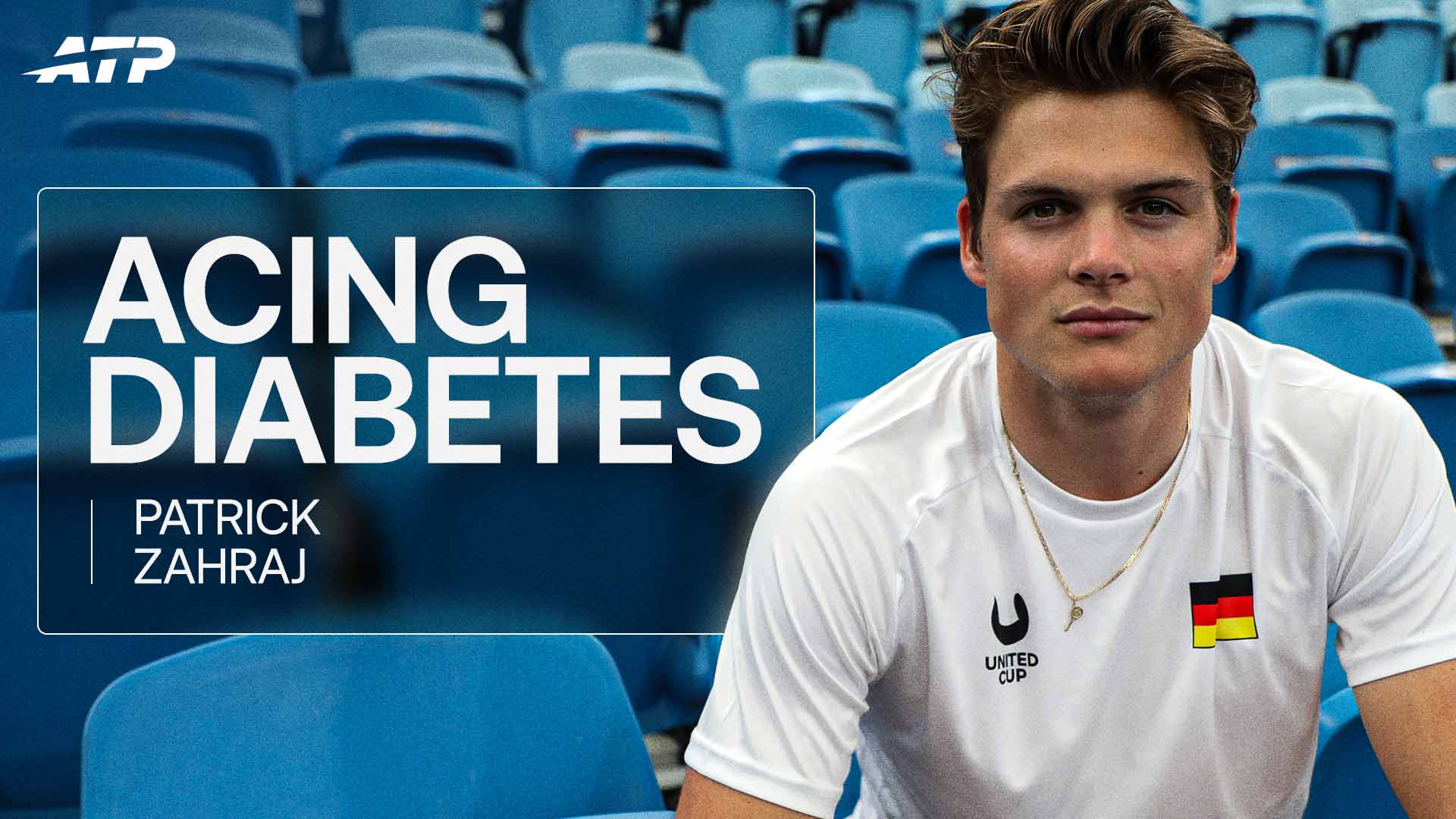

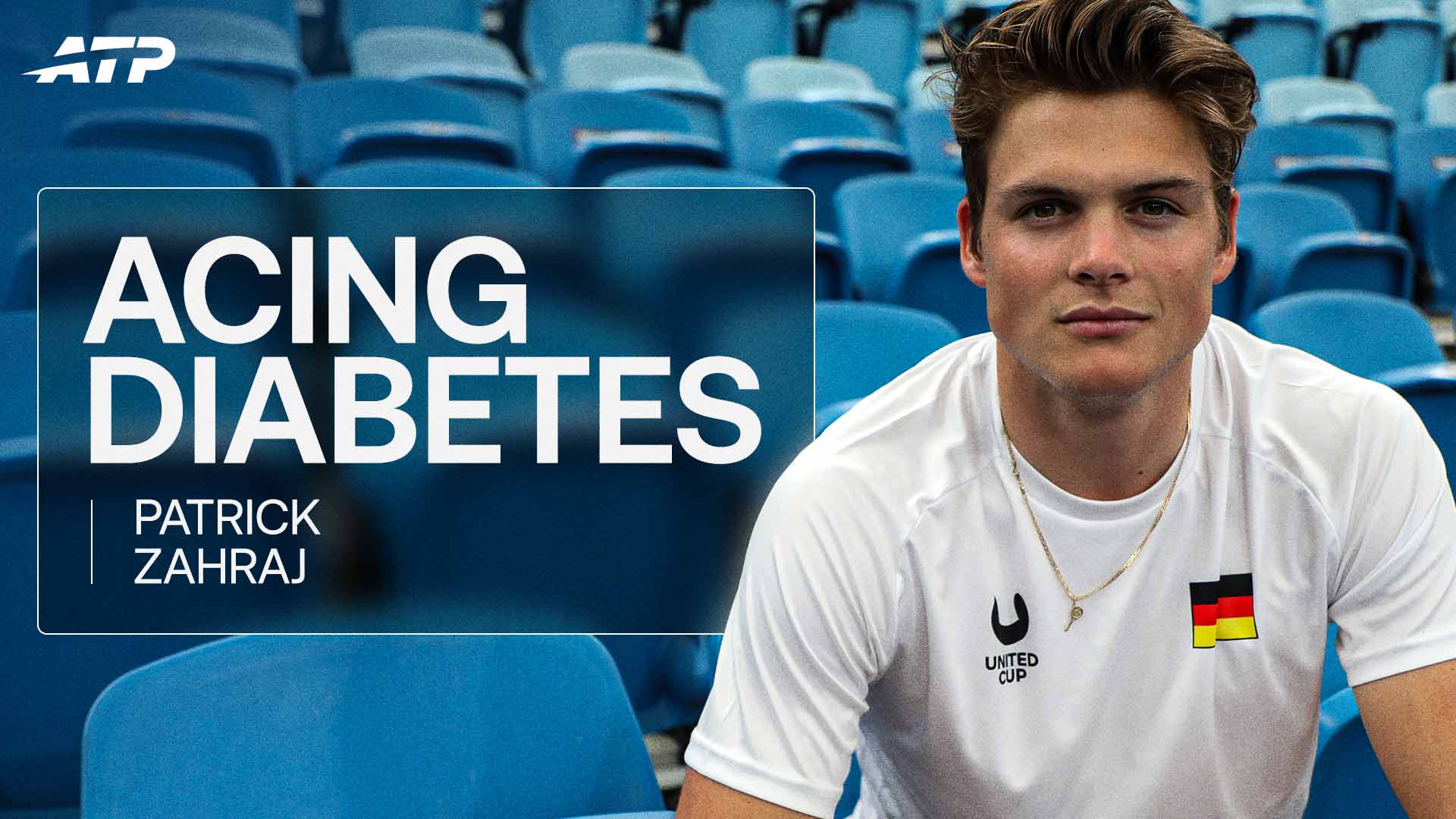

This week I am at the United Cup on Team Germany, which also has another Type 1 diabetic: Alexander Zverev.

Sascha has been a big inspiration for me. He is two years older and my early contact with him as a kid was very important, especially for my parents, who had a couple of phone calls with his parents. Sascha was diagnosed with diabetes earlier than I was and already had experience to show it was possible to still chase dreams despite living with the disease.

Their family was able to explain to us that it was doable with some hints here and there. That was motivating for me to pursue the path of becoming a professional tennis player and just see that it was possible. It was so relieving for a young athlete, like I was back then.

Once Sascha went public with it in 2022, launching the Alexander Zverev Foundation, it was such a huge factor for the Type 1 community. So much work can still be done and we can motivate people and share our experiences to show the world what is possible. For the kids who are diagnosed, we can hopefully provide hope.

Despite living with this, I have still become one of the Top 250 players in the world. My dad, Radek, was a pro who reached World No. 277. Growing up, I saw him playing and competing, so chasing this dream was always in the back of my mind.

When I was in the hospital for a month, my dad was coaching a couple of pros, including four-time ATP Tour doubles titlist Andre Begemann. They came to visit me in the hospital, and we built a tennis net out of big Lego blocks. It was pretty cool to see all of us coming together and just trying to pass the time with some tennis in the hospital, because there was a lot of dull downtime outside of learning about the disease.

Once I was diagnosed with diabetes, the first conversations with my doctors did not go well in terms of my tennis hopes. They were actually not that supportive in terms of playing tennis in general. The medical experts said there was high risk for severe low blood sugar among other things.

Some doctors were unable to help us and some gave us some hope that it would be possible to compete. It was a lot of trial by error. There is a lot that goes into being a professional tennis player and even more doing all that while thinking about things like glucose intake, figuring out which carbohydrates work the best and quickest for me and worrying about my blood sugar.

I went on to play college tennis at UCLA, where I was a two-time All-Pac 12 honouree and a two-time ITA Scholar-Athlete. From there, I embarked on playing professional tennis.

I have an insulin pump with two attachment points in the back of the gluteus maximus. I have a sensor in my tricep for which I need to switch triceps every 10 days. I switch infusion sites every two days and insulin cartridges every four to five days.

While I am focused on my game and strategy, I also have to consider my blood sugar monitoring and levels. If the connection between my sensor and my phone is not working, or there is a technical error when I’m on court, that is a problem. All of a sudden you get to the bench and see, ‘Dang, I have no connection so I don’t know what my sugar is doing right now’. I don’t know what the trend is and that could impact me.

I have the glucometer as a backup so I can manually check my levels and make decisions as far as what to eat and when. There is always an extra layer.

We’re out on the court so we want to manage our body for peak performance, but when our blood sugar is already high and we’re at a stage of the match like a second-set tie-break when you feel you need a bit more energy, you cannot eat at that point because your blood sugar is already high. You want to have your best performance, but you also have to manage your diabetes. It is a juggling act.

Last year I was facing Kyle Edmund at an ATP Challenger event on grass in Nottingham. With my levels, I injected manually multiple times to try to balance my numbers and nothing was working. I ended up overcompensating and suddenly I was stumbling to make it to the side of the court. I nearly blacked out and was offered medical assistance just to get off the court.

I retired from the match and the next morning was on a plane to Basel, where my dad picked me up to drive me three hours to Gstaad. I went from dealing with a diabetic episode on slick grass to competing on clay at altitude at an ATP Tour event, where I would compete in my first tour-level main draw.

Living with diabetes requires a lot of attention, but after 17 years of having it, it becomes routine. I learned a lot through the years and I'm glad I went through the whole process to get me to the point where I am right now, where I feel fully comfortable with the disease.

There are some positives, too. Diabetes has helped me build incredible discipline from a young age. Aged nine I was already calculating all my insulin shots by myself in school, which really made me independent. Otherwise, I would have needed a babysitter all the time. And then there is the mental factor of acceptance and getting past things pretty quickly to find solutions. Things don’t always go our way. You might not know your schedule, or have to deal with a flight delay or jet lag. So many things can affect your blood sugar — it is like fighting with waves, which you try to minimise the best you can. Life is never going to be a straight line.

But I want people with diabetes reading this to know that there is always a way. It might be a different one for every individual. I have different problems than Sascha has physically, for example. But what I have found over the years of having this disease is that there is always a way, as long as you’re willing to put in the effort and reach out to people in order to learn. You can transcend that lesson to life as well, but especially for the Type 1 community.

The more we share together, the more we can learn and optimise our disease together to live freely without constraints.

- As told to Andrew Eichenholz

Read More My Point first-person essays