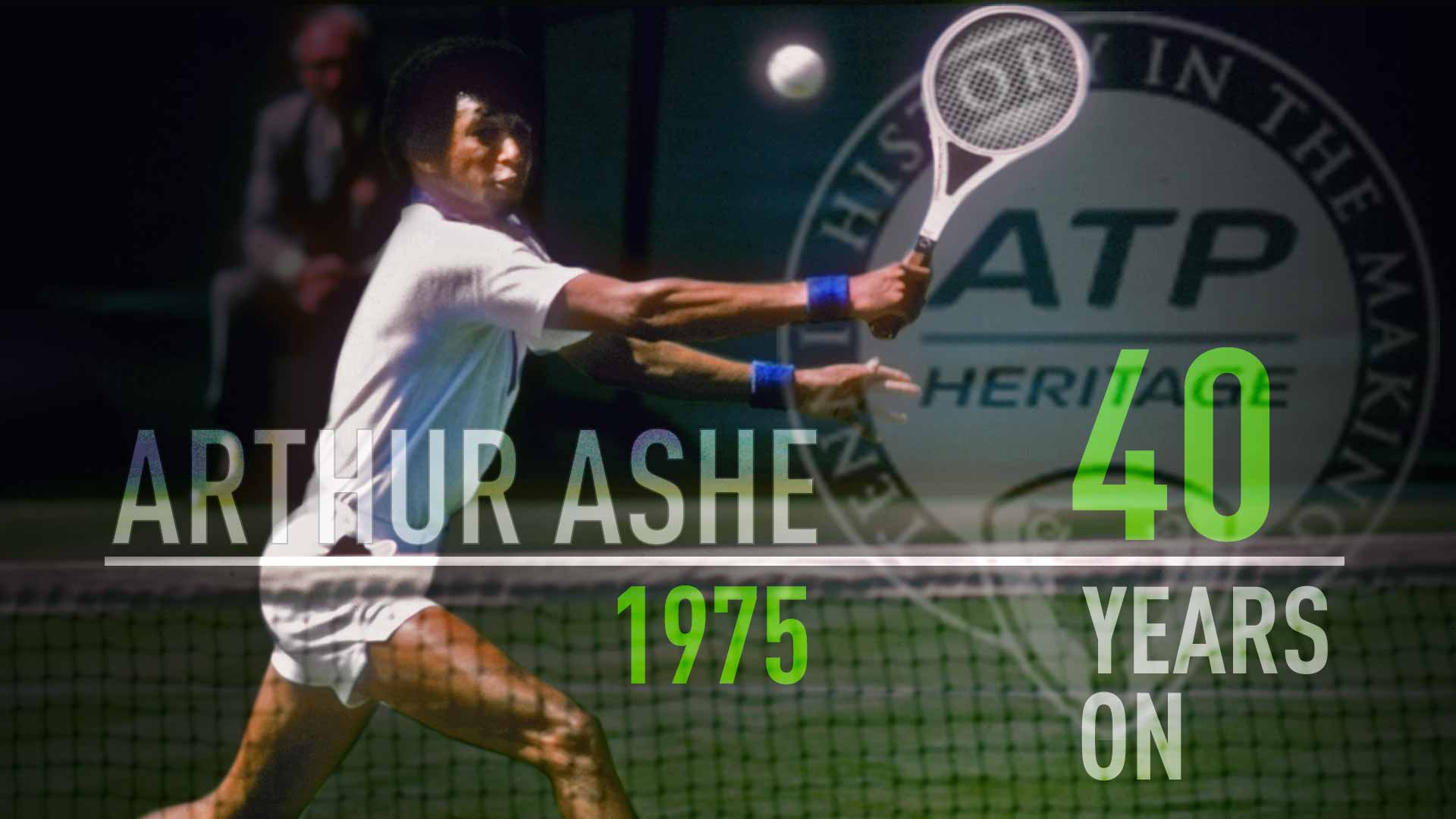

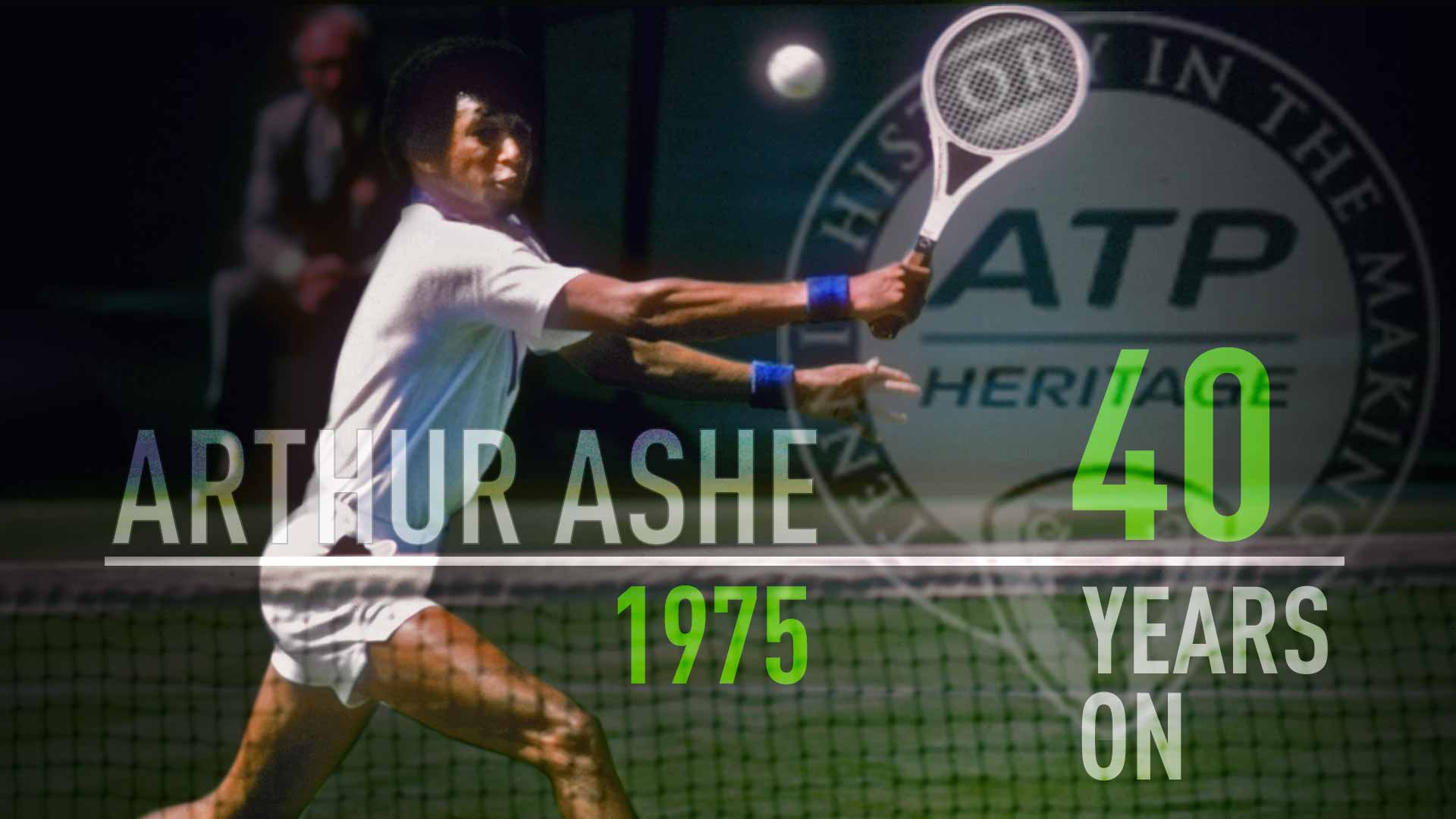

On Saturday, 5 July 1975, Arthur Ashe recorded his greatest triumph on a tennis court. With exclusive insight from Ashe's closest friends, James Buddell of ATPWorldTour.com recounts how the American lifted the Wimbledon trophy — one of the most significant wins in the sport’s history.

As 2 p.m. draws closer, Ashe and Connors are relaxed in the locker room. Gloria Connors, Jimmy’s mother, his agent Riordan, and the actress Susan George sit patiently in the players’ box. Ashe’s best friend, physician Doug Stein, who learned of Ashe’s game plan a few hours earlier, sits beside Dell and his wife, Carole, and Riessen. Ashe has told Stein over an early breakfast, "I have this strange feeling that I just can't lose today." Arthur Ashe Sr., his father, has had a heart attack the previous November, so is at home in Richmond, Virginia. Twynam, the groundsman, is to be found on a fold-up chair in the walkway below the Royal Box. There’ll be no need for him to curse the 'toe-draggers' today.

Bud Collins is courtside with Jim Simpson, ready to go on air in a live NBC television broadcast. “I remember being very nervous for Arthur before the match, worried that Connors would humiliate him,” says Collins, now aged 86. “Being litigants in a $40 million lawsuit didn’t help. It would prove to be an emotionally charged match.”

“No one really thought that he could win that match because Connors was playing so well and had won the year before,” admits Stan Smith, the 1972 Wimbledon champion.

Connors and Ashe wait until attendant Peter Morgan gives them the nod to leave the small waiting room, beside Centre Court. Leo Turner, carrying their bags, walks closely behind them. They all pause to bow to the Duke and Duchess of Kent as photographers swarm around George Armstrong’s chair. “When I walked on court, I thought I was going to win,” said Ashe. “I felt it was my destiny.”

Five days shy of his 32nd birthday Ashe wears a navy blue Davis Cup jacket, with U.S.A. embroidered in red on his left breast. The significance is not lost on anyone. Connors, aged 22, wears a white Sergio Tacchini jacket. He has yet to represent the United States in the Davis Cup. Connors sits with his back to Ashe, who has pointed his chair on an angle facing the court. It is the first year that chairs had been provided for the players, beside the umpire’s chair.

The pair’s fourth meeting begins. It’s the first all-American Wimbledon final since 1947, when Kramer beat Tom Brown.

Connors, nursing an injured knee, wins the first game. At the end of the third game, Dell remembers watching Ashe sit down and reach for one of his racquet sleeves.

“After the third game, he pulled out the envelope from his racquet cover. I could not believe it. I was surprised. It’s the Wimbledon final, and he’s reading and studying it. The press thought he was meditating. There was a buzz around Centre Court, asking what was he doing? He was reading.” Barrett recalls, “Connors, too, was reading notes from his late grandmother [Bertha Thompson, ‘Two-Mom’] that were on pieces of paper tucked into his right sock.”

The first set is won in just 20 minutes. Having lost the first game, Ashe wins the next nine. His strategy is working to perfection.

At 0-3 in the second set, a voice yells out. “Come on, Connors!”

"I'm trying, for crissake!" the defending champion replies.

The second set passes by in a flash. Ashe leads 6-1, 6-1. He looks up at the clock, it’s 2:41 p.m. He sits motionless, sometimes with a green towel over his head, serious and poised. Afterwards, Ashe explains, “I let every muscle go limp for 45 seconds each changeover.”

Connors withstands four break points, clinching the third set 7-5 with a forehand winner, as Ashe momentarily reverts to his natural game. It’s a gritty attempt to come back. The top seed then races out to a 3-0 lead in the fourth, courtesy of backhand winners down the lines. But Ashe regroups, breaking back in the fifth game – sticking to the game plan.

Collins says, “He played a match of technical magnificence, changing speed, feeding junk to Connors’ forehand, slicing his serves wide to Connors’ backhand, cleverly mixing up his game the entire match.”

Having broken Connors for a 5-4 lead, Ashe was serving for The Championships.

Three of Ashe’s first four serves are returned into the net.

“On match point at 5-4, 40/15, Arthur sliced a ball out wide to Connors’ backhand,” says Dell. “The response was feeble.” The last shot, a smash, was struck into the open void. It ended the two-hour, five-minute encounter.

“Arthur whirled around and clenched his fist. Many thought it was a ‘Black Power’ salute, but it was a personal gesture. It wasn’t Arthur’s style.”

Photographers flood the court, shortly after Armstrong announces the final score, 6-1, 6-1, 5-7, 6-4. Connors and Ashe shake hands. It is fleeting. No words are exchanged.

“The tactics may have looked suicidal,” said Ashe post-match, “When I took match point, all the years, all the effort, all the support I had received over the years came together.”

During the historic final, a 12-year-old Zina Garrison is darting in and out of the pro shop and onto Court One at MacGregor Park in Houston, Texas. Garrison recalls, “We would hit a little then run into the pro shop watch a little, and then go back and try to hit one of the shots we just saw him hit. When he won, we were all Arthur for a day, and lots of pride from that day on. If he could play at Wimbledon so could we.” Garrison went on to reach the 1990 Wimbledon final, which saw Martina Navratilova clinch her ninth title.

Billie Jean King sat directly opposite the Royal Box. She’d routed Evonne Goolagong 6-0, 6-1, a day earlier. It was her sixth Wimbledon title and afterwards she announced her intention to retire from singles competition. “Without a doubt it was the match of Arthur’s life,” says King. “The match was one of the few men’s finals I ever saw at Wimbledon live… He had made history as the first man of colour to win Wimbledon and I think that meant a great deal to him. Of course, the great Althea Gibson had broken that barrier for all of tennis almost 20 years earlier.”

“Ashe's win stripped away the aura of invincibility that Connors carried into that final,” recalls veteran tennis writer Evans, the ATP European Director in 1975. “He was never going to be considered the best player of all time – there were weaknesses in his game, [such as his] low and short forehand that Ashe exploited so brilliantly. Ashe's achievement was, in my opinion, one of the most remarkable in sport. To go into the most important match of your life and adopt tactics that were completely contrary to your nature and style was an extraordinary feat, not least because he stuck to the plan and didn't panic when Connors won the third set.”

At an ATA (American Tennis Association) Championships in New Haven, Connecticut, officials stop play as African-American players celebrate. Thousands of miles away, in the swell of emotion, Lew Hoad was waiting on the telephone, wanting to offer his congratulations from his villa in the south of Spain, as Ashe left Centre Court. Don Budge, the 1938 Grand Slam champion, expressed the belief that, “Ashe was the first one to play Connors the right way, to put the ball where his reach was limited." In fact, many had succeeded to beat Connors with the tactic since juniors. When Collins interviews Ashe afterwards, the journalist remembers, “We had smiles as big at the Mississippi River.”

That evening, Connors takes a helicopter to Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire, to attend a Neil Diamond concert. Ashe dances with King at the Wimbledon Champions’ Ball. King remembers, “Afro hairstyles were very popular that year and Arthur and I both had afros in 1975. We had a chuckle during the traditional champions’ dance when I told him, ‘At least your afro is natural.’ That night was a big deal for him – his first Wimbledon championship – and I remember him soaking everything in and being more expressive than he was normally.”

Ashe’s tennis legacy was complete. “It really was a second resurgence,” recalls Smith. “He played one of the best strategic matches of all time,” says Pasarell. “It was unlike Arthur's game, but the fact that he implemented something that was foreign to him; the fact that he could execute it, was amazing.”

The victory exemplified his maturity in tactics. He’d earned £10,000 in prize money, but was infinitely richer. With the Wimbledon trophy in his hands, it defined him as a tennis player. Connors’ lawsuit against Ashe is soon dropped.

McNair, having missed the final, lands in Dallas and gets picked up by his mother.

“I was so excited to find out he had won,” says McNair, who then waits until Arthur returns to New York.

“So I call Arthur…

“’Arthur, it’s Fred. It’s unbelievable. Oh my God. I’ve got to come up there. What in the hell? I read Barry Lorge in the [Washington] Post.’

“’Fred, will you shut up?’

“’Fred, I got back from the Wimbledon Ball and James [the concierge] is at the front desk. He gives me an envelope and I open it.

“It read, ’Meet me for breakfast, 9 a.m. sharp. Barclays Square. Richard Burton.”

“It captured the little boy in Ashe,” says McNair.

“’Can you believe it, Fred?’” says Ashe. “’Richard Burton wants to have breakfast with me.

“’I’ve got 100 pounds to collect!”

Go Back To Part I | Go Back To Part II